Background

Until recently, the rapid growth of the digital economy had relatively few implications for energy demands and carbon emissions. But the landscape has shifted dramatically with the explosive rise of generative AI, accelerated by the launch of ChatGPT in October 2022. This surge is driving a sharp increase in demand for data centres, reshaping how energy is supplied around the world and increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

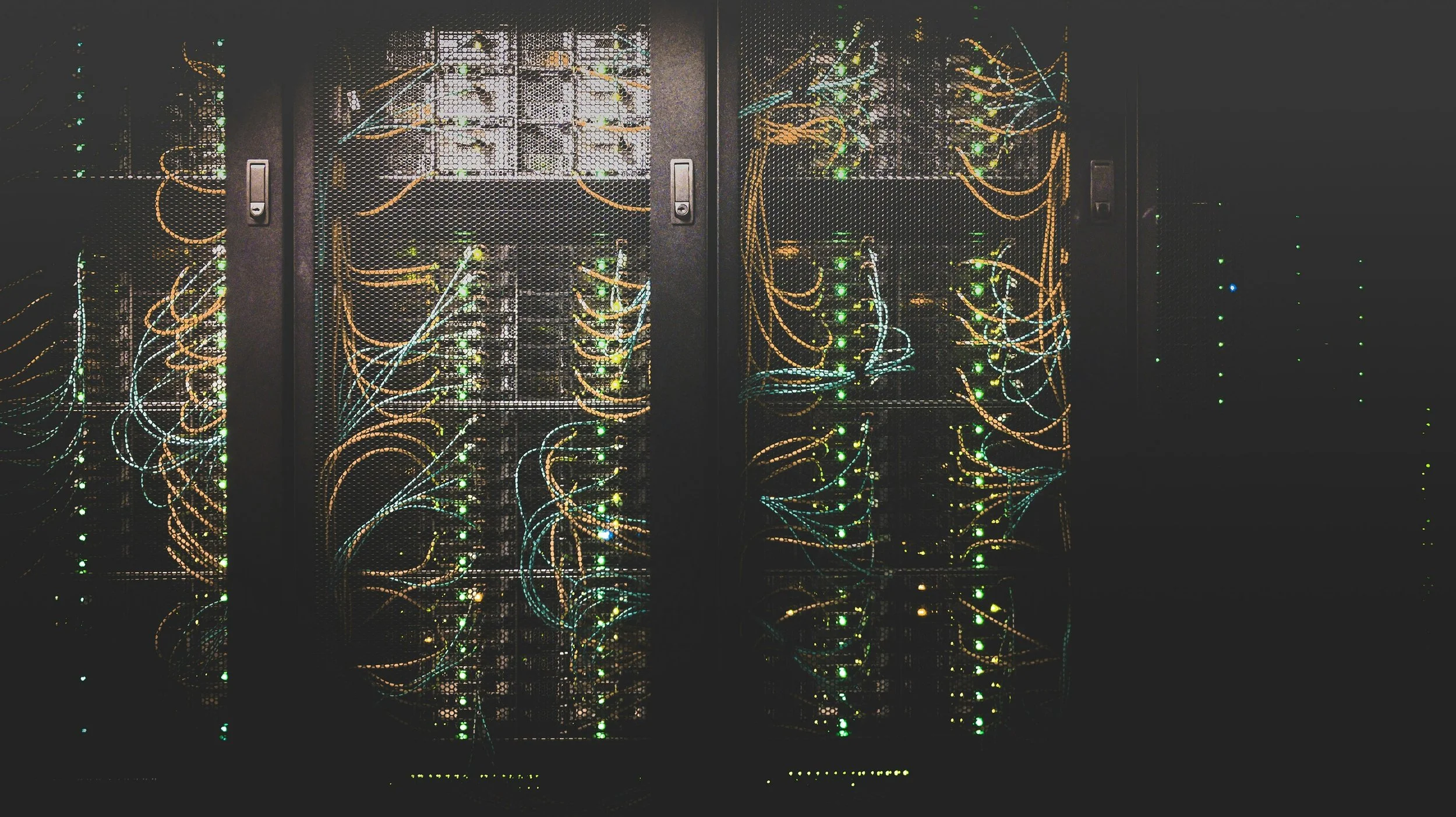

Data centres are specialised locations containing hundreds, if not thousands, of dedicated servers, collecting, processing and transmitting data that make the applications of the modern internet function. Data centres need semiconductors to provide computing power, electricity to power computing and other operations, and water to cool those machines down to an efficient temperature. The policy response in the developed world is great enthusiasm for the rapid expansion of data centres, but this comes with little thinking about how to meet the resulting energy and water demands.

In theory, the sector’s power needs could be almost entirely met by renewable energy. In practice, it isn’t. Natural gas and even coal are often seen as the cheapest and most reliable energy sources for data centres. The United States, for instance, uses natural gas to feed 60% of the new electricity demand coming from data centres. Germany and Poland are extending the life of coal-powered electricity plants to supply the growing number of data centres.

The scale of the problem

- Globally, building and running new data centres uses about the same amount of electricity as France or Germany.

- Data centres today are responsible for at least 0.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- According to the International Energy Agency, in five years, data centres are likely to account for 1.4% of global emissions – a footprint the size of Japan.

- The largest “hyperscale” data centres use 3-5m gallons of water per day – about the same daily consumption as a town of 40,000 people (a hyperscale centre would be at least 10,000 square feet, consuming 20-50 MW of power. Only the largest companies, like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft and Google, are likely to be able to afford the costs of building at this scale).

What’s covered in the report?

Our report, Data centres: how soaring demand threatens to overwhelm energy systems and climate goals, outlines the key challenges associated with AI-driven data centre growth. It finds that:

- So far, governments and regulators have largely left Big Tech and data centre operators to set their own voluntary decarbonisation targets.

- With AI adoption surging, and its future impact only set to grow, a hands-off approach no longer works. Regulation is urgently needed to reduce emissions and maintain the stability of electricity supplies.

- Data centre profits overwhelmingly flow to a small number of companies typically in the Global North, while local populations suffer from their high resource demands for energy and water – and see few benefits. This is neocolonialism in action.

Our recommendations

The report sets out the following initial recommendations for how governments can respond:

- Conduct official national and supra-national assessments of the likely paths of energy use, and subsequent emissions from data centre expansion. Cross-refer these scenarios against the national and supra-national frameworks for emissions control, such as the UK’s Carbon Budget system.

- Consider the legal, regulatory and policy changes needed to switch data centre power supplies to 100% renewable energy. This should apply to the whole process: from construction to operation to battery storage.

- Minimise the footprint of data centre operations by developing policy to reduce data collection, processing and storing.

Learn more by downloading our policy briefing below.