Why is shipping a problem for climate change?

The growth in consumerism has fuelled an enormous growth in getting goods shipped around the world since the pandemic. So much so, that shipping now accounts for more than 80% of international trade by volume (UNCTAD), and in the UK more than 95% of all imports and exports are transported by ships (UK Chamber of Shipping). And that’s before we even consider the impact of shipping pollution from the likes of cruise ships, fishing vessels and military fleets.

All this activity makes it a major player on the climate crisis leaderboard too. Shipping is responsible for 3% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions every year, which may not sound significant, but it is roughly equivalent to the entire emissions of Japan.

And it is growing. In the period between 2016 and 2023, shipping’s CO2 emissions grew by 10% and methane emissions grew by more than 150%, according to ICCT’s Global Shipping Emissions 2016–2023 report.

Unless it takes further action, shipping’s GHG emissions are expected to grow by 16% from 2018 to 2030, and by 50% by 2050. To put it plainly, if we continue as we are, the shipping industry could account for 10% of all GHG emissions by 2050.

What impact do shipping emissions have on the environment and human health?

Shipping emits 1,000 Mt CO2 emissions per year – the same emissions as the annual average use of around 1.5bn homes.

But it’s not only CO2 emissions that are a concern – shipping is also responsible for a whole host of environmental harms. These include:

- Methane – an extremely potent GHG, which has climate impacts over 80 times greater than CO2 over a 20-year period.

- Nitrous oxides (NOx) – a GHG 273 times more potent than CO2 over a 100-year period.

- Black carbon – soot, which warms the atmosphere when emitted but also warms the planet when it lands on reflective surfaces like snow or ice, making them darker and less able to reflect incoming solar radiation. Black carbon emissions from Arctic shipping could have an especially large climate impact.

- Air pollutants – sulphur oxides (SOx), black carbon and particulate matter (PM), which are extremely problematic to human health. Exposure to these shipping pollutants causes health risks such as respiratory and cardiovascular disease. It’s estimated that shipping pollution contributes to tens or even hundreds of thousands of premature deaths worldwide each year, with those living close to ports and shipping lanes particularly affected.

- Other forms of pollution – shipping is also responsible for environmental harms caused by invasive species, oil spills, wastewater and noise pollution.

What is the shipping industry doing to reduce its pollution?

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is the global regulator for the industry. Its Member States are in the process of negotiating the adoption of a major new regulation called the IMO Net-Zero Framework (NZF), which aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping.

The discussions on adoption were adjourned in October 2025 but will be reconsidered in 2026. If adopted, the NZF will introduce a two-tier global fuel standard (GFS) that includes partial emissions pricing and rewards for ships using cleaner fuels or technologies (called ZNZs – zero or near-zero emission sources).

Plus, a dedicated IMO Net-Zero Fund would collect revenues from emissions pricing and redistribute them for ZNZ rewards and to support a just and equitable energy transition for climate vulnerable states including Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

Find out more in our guide to the IMO Net-Zero Framework.

How can we reduce shipping emissions?

Reducing the industry’s GHG emissions is essential, and can partly be achieved by measures including:

- Demand reduction

- Energy efficiency improvements

- Use of wind-assisted propulsion

- Speed reduction

- Electrification

However, decarbonisation will also rely on replacing climate-damaging fossil fuels with lower emission alternative fuels.

Alternative fuels for shipping: what works and what doesn’t?

Decarbonising shipping will require replacing fossil fuels, but not all alternatives deliver real climate benefits.

False solutions

- Liquefied natural gas (fossil LNG): Often promoted as a “cleaner” marine fuel, fossil LNG is primarily methane – a greenhouse gas over 80 times more potent than CO2 over a 20-year period. Methane leaks across the LNG supply chain significantly undermine any climate benefits, making LNG incompatible with the 1.5°C Paris Agreement goal. Read more in our report: (Un)sustainable from ship to shore.

- Biofuels: Scaling biofuels for shipping is neither economically nor environmentally sustainable. Large-scale use would intensify pressure on land and biodiversity and risks damaging nature restoration efforts over the coming decades. Read more in the SASHA Coalition’s report: How e-fuels can mitigate biodiversity risk in EU aviation and maritime policy.

Potential zero-emission alternatives

E-fuels are produced using renewable electricity and can reduce lifecycle GHG emissions by up to 90% compared to fossil fuels.

- E-ammonia: When used in ship engines, ammonia does not emit CO2. To deliver genuine climate benefits, however, it must be produced using renewable energy, and emissions of nitrous oxide, hydrogen and reactive nitrogen must be tightly regulated. Read more in our report: Ammonia as a shipping fuel.

- E-methanol: Already gaining market traction, e-methanol can achieve up to a 94% reduction in carbon equivalence compared to fossil fuels, with growing uptake across vessels and ports.

Read more in our guide to alternative fuels.

Which policies help to reduce shipping emissions in the EU and the UK?

European shipping is regulated mainly by two pieces of legislation, the Emissions Trading System and FuelEU Maritime.

How the EU Emissions Trading System regulates maritime emissions

The EU emissions trading system (ETS) makes industry pay for its emissions. It has included maritime greenhouse gas emissions from the largest vessels since 2024, and extends to methane and nitrous oxide from 2026.

Each year the upper limit of emissions the sector can release decreases incrementally, incentivising ships to gradually reduce emissions to avoid paying penalties. Companies reducing quicker can sell allowances to those that are slower, creating an extra incentive to make the transition to less-polluting systems.

The ETS covers all emissions from domestic voyages and 50% from international voyages (those between European and non-European ports).

The EU ETS is important for putting into practice the polluter pays principle, where those responsible for pollution are obliged to pay for that pollution. It also generates revenues, which can be used to drive climate action, such as investing in burgeoning clean technologies, or contributing to international climate finance commitments.

FuelEU Maritime: boosting renewable marine fuels

The FuelEU Maritime regulation aims to boost demand of renewable, low-carbon fuels and clean energy marine technologies. It sets maximum limits for the average GHG emission intensity of ships arriving in EU ports. This decreases gradually, starting at 2% in emission intensity in 2025 and reaching up to an 80% reduction by 2050.

The gradually lowering limit incentivises investment in sustainable technologies like marine e-fuels, or renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs). The regulation encourages special incentives being introduced for these fuels, reflecting their heightened role in decarbonising the sector.

The regulation also obliges ships to use on-shore power supplies or alternative green sources to reduce pollution when harboured in ports.

Both the EU ETS and FuelEU Maritime only apply to large ships of 5,000 gross tonnage (GT) and above. Opportunity Green supports the extension of the scope to all ships over 400 GT in the 2026 review of the EU ETS in order to drive decarbonisation amongst those smaller, but still significantly-sized vessels.

The UK Emissions Trading Scheme and the Maritime Decarbonisation Strategy

UK shipping is regulated by the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and further policies have been suggested in the Maritime Decarbonisation Strategy.

Maritime GHG emissions are included in the UK ETS from 2026. Like the EU ETS, it requires ships to pay for all their pollution and a penalty on those that exceed the emissions cap in a given year.

The UK ETS applies to ships of 5,000 GT and above, but unlike the EU ETS it only covers domestic voyages between two UK ports and not journeys made between UK and non-UK ports. However, the government has recently committed to expanding the UK ETS to include emissions from international voyages, subject to public consultation.

The Maritime Decarbonisation Strategy was launched in March 2025, replacing the Clean Maritime Plan. The Strategy aligns the UK with the IMO’s 2023 Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships to achieve zero fuel lifecycle maritime greenhouse gas emissions domestically by 2050, with interim targets.

What does international law say about shipping pollution?

In international law, pollution of the marine environment by ships is governed primarily through the IMO’s International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). This sets out specific regulations for the shipping sector to prevent or minimise pollution from ships, with Annex VI covering emissions resulting in air pollution and climate change.

Additionally, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) contains obligations on States to protect the marine environment from climate harm caused by GHG emissions, including emissions from the shipping sector. This was reinforced by the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), which clarified in its 2024 advisory opinion on climate change that States need to take all necessary measures to prevent, reduce and control marine pollution caused by GHG emissions. This includes taking individual (domestic) action as well as participating in global efforts.

Read more in our legal briefing: The ITLOS Advisory Opinion on States’ obligations in relation to climate change and the marine environment.

Other more general environmental legal regimes also apply to shipping pollution. For example, the Paris Agreement calls for global efforts to keep the average temperature increase to 1.5°C and applies to all sectors, which means reducing GHG emissions from international shipping. The world’s highest court, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), confirmed in its 2025 advisory opinion on climate change that the Nationally Determined Contributions of states submitted pursuant to the Paris Agreement should reflect the highest possible ambition and requires actions across all economic sectors, including international shipping.

As shipping’s emissions continue to grow, these legal obligations risk being unmet, which is likely to fuel the mounting legal pressure on the industry to decarbonise. The International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) has warned that climate change litigation could herald a new legal risk for shipping companies and directors, as plaintiffs seek to hold countries, local authorities and private actors accountable for climate harms.

Read more in our legal briefing: Climate change litigation and shipping: taking stock which identifies more than 30 cases targeting the shipping sector.

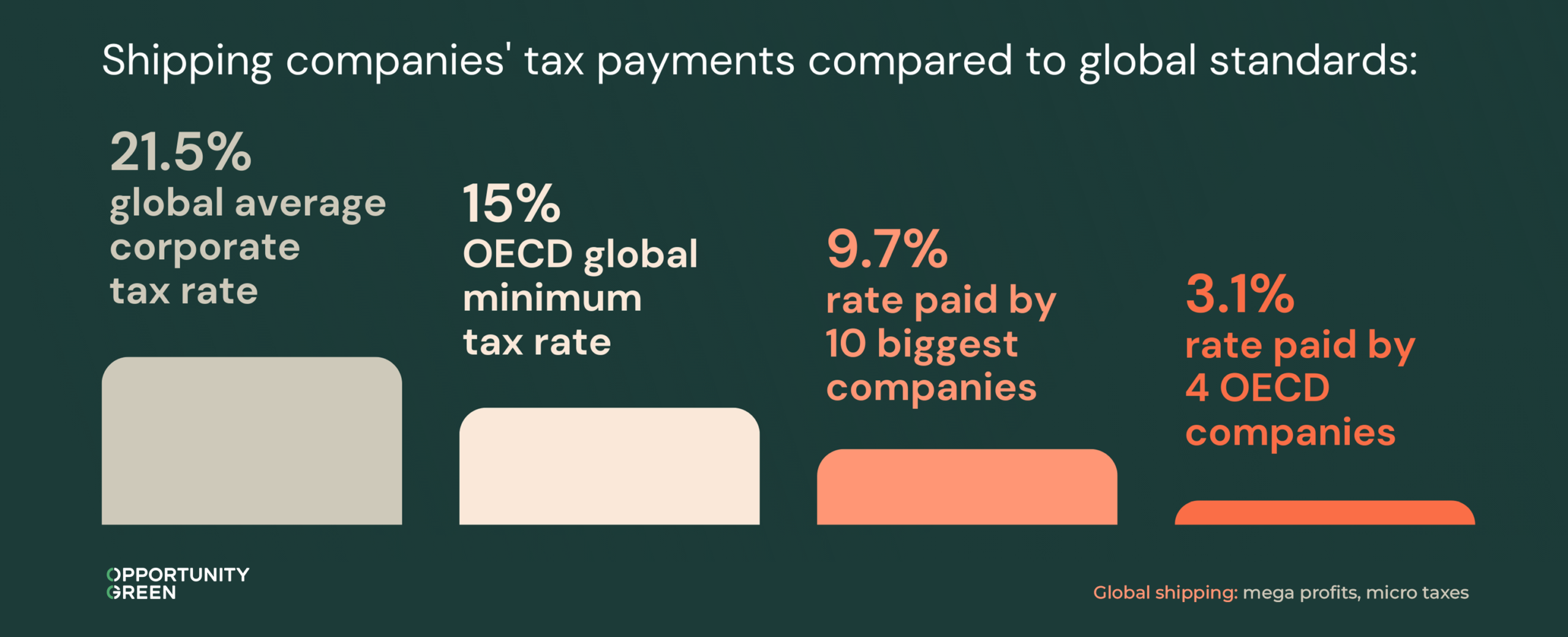

How much tax do shipping companies pay?

The short answer: not enough. The world’s 139 largest companies made over $300bn in profits from 2019-2023. Of this huge sum, 93% was taken by just the top 10 largest companies. Yet these same companies paid only $30bn in tax, an effective tax rate of 9.7%. This is far below the global corporation tax average rate of 21.5%, and below the new Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) global minimum tax rate of 15% (from which shipping is exempt).

Read more in our report: Global shipping: mega profits, micro taxes.

Although the idea of introducing a GHG levy within the shipping industry has been on the negotiation table at the IMO for some time, the industry is now debating the IMO’s Net Zero Framework (NZF).

The NZF includes partial emissions pricing, which if it had been adopted in October in 2025 was estimated to generate around $10-15bn per year from 2030. However, this is a very limited pot of money compared to other more ambitious proposals previously put forward, which would have gone much further for ensuring a just and equitable transition for the industry.

Learn about our approach to tackling shipping’s climate impact.